"The son did as he was told. All his bloody life, he has done as he has been told. Time to change that, he thinks, grabbing a pen. He doesn't write that this will be the last time his father stays here. He doesn't write that he wants to break the father clause. Instead, he writes: Welcome, Dad. Hope you had a good flight."

A grandfather who lives abroad returns home to visit his adult children. The son is a failure. The daughter is having a baby with the wrong man. Only the grandfather is perfect—at least, according to himself.

But over the course of ten intense days, relationships unfold and painful memories resurface. The grandfather is confronted by his past. The daughter is faced with an impossible choice. The son tries to write himself free. Something has to give. Per a longstanding family agreement, the grandfather has maintained his Swedish residency by coming to stay with his son every six months. Can this clause be renegotiated, or will it chain the family to its past forever?

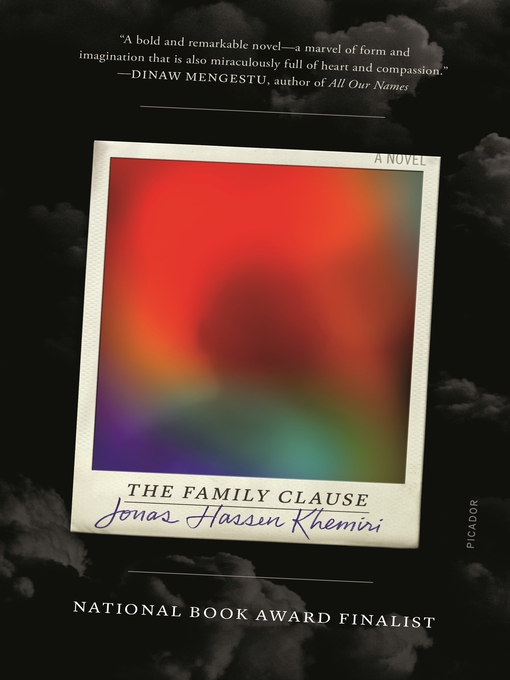

Through a series of quickly changing perspectives, in The Family Clause Jonas Hassen Khemiri evokes an intimate portrait of a chaotic and perfectly normal family, deeply wounded by the death of a child and the disappearance of a father.

-

Description

-

Creators

-

Details

-

Reviews

- Jonas Hassen Khemiri - Author

- Alice Menzies - Translator

Awards:

Kindle Book

- Release date: August 25, 2020

OverDrive Read

- ISBN: 9780374719616

- Release date: August 25, 2020

EPUB ebook

- ISBN: 9780374719616

- File size: 1592 KB

- Release date: August 25, 2020

Loading